Humans are no strangers to the Sandhills. Long before cowboys drove their cattle to graze on its grasses and before Kinkaiders settled the area, people were here. Indigenous groups have continuously used the area for at least thirteen thousand years, hunting its game, gathering its plants, and drinking its water. They experienced the region’s winds and temperature swings. They endured its storms and its droughts.

We know the experiences of these early Great Plains inhabitants through the material traces they left behind. These items and places are tangible reminders of living communities both past and present, evidence of which has been found by researchers and residents alike. Archaeologists have been probing the region for nearly a century in search of evidence of these people and their day-to-day lives to develop a better understanding of ancient habitation of the area. Increasing our understanding of these groups can be complicated, however, as much of their story lies in abandoned places and in artifacts hidden beneath the sand in thick dune fields and dense grass. The complex geologic and vegetational history of the Sandhills is a mixed blessing for archaeologists. With ancient land surfaces quickly covered by blowing sand, the places occupied by the area’s earliest inhabitants may be extraordinarily well-preserved yet equally difficult to find and study. Many of the earliest traces of these groups have only been found by chance occurrence on the modern surface, exposed through erosion in blowouts or along roadcuts.

Little is known of the earliest people to enter the Sandhills region. Objects from this period have been isolated finds, which simply demonstrates that people were in fact here. The oldest artifacts found are Clovis spear points used to hunt mammoths and other now-extinct animals over thirteen thousand years ago. Over the course of the next ten thousand years, human occupation of the region continued, although it certainly ebbed and flowed as climatic and environmental conditions changed. A variety of later spear point styles dating from twelve thousand to two thousand years old have been found throughout the region and provide evidence that a myriad of ancient hunting-gathering Indigenous populations frequently lived and hunted in all areas of the Sandhills, with bison having become the predominant species on the plains. Additional information about the lives of these early inhabitants can only be gleaned from nearby sites. Other than a few burials on a remote McPherson County lakeshore and a small campsite in Sheridan County, no intact archaeological sites dating to this period have been discovered in the Sandhills. Materials found at these neighboring sites suggest that in addition to bison, these central plains peoples were hunting a wide variety of smaller game, collecting plant foods, and were involved in sophisticated long-distance trade networks.

Then, about two thousand years ago, things began to change. The number of intact habitation sites increased significantly, suggesting population growth. While this increase may be more apparent than real, with earlier sites more obscured from discovery by overlying sand dunes, this period of remarkable change is further defined by new technologies and cultural practices. Groups were becoming more sedentary, constructing small, semipermanent villages with storage systems to support longer-term occupations. These people, influenced by the Woodland Tradition of the Midwest, were the first Indigenous people to make pottery and experiment with horticulture. Deer, bison, turtle, bird, beaver, rabbit, domestic dog, and many wild plants were all food sources being consumed at small habitations found along Sandhills lakes and the Middle Loup River.

An even greater influx of people and ideas began a thousand years ago. These immigrants came from the south and were the distant ancestors of the Pawnee, Arikara, and Wichita, the first people who can be directly associated with named tribes. They lived across most of Nebraska, northern Kansas, and western Iowa, and they regularly ranged into the eastern and central Sandhills. Places like the McIntosh site in Brown County provide a glimpse into the daily lives of these people, as they occupied a small village along a Sandhills lakeshore. Here they resided, hunting and fishing over fifty bird, fish, turtle, and mammal species, gathering wild plants like chokecherries and plums, and growing domestic plants of their own, including squash and corn. The remains of their meals, their pottery, and a broad variety of stone and bone tools have been found hundreds of years later in the many storage and trash pits located across the site.

Due to climatic deterioration and related social pressures, human population in much of Nebraska dwindled significantly in the 1400s and 1500s. However, by the mid-1600s, Apaches had begun to travel and settle across the vast areas of western Nebraska and the Sandhills, occupying the region during their long migration from the subarctic to the Southwest. These hunters focused primarily on the area’s bison herds, but deer, pronghorn, turtle, small mammals, and mussels were also captured and eaten. Plains Apache horticulture and plant gathering was limited, but charred remains of squash, gourd, corn, plums, chokecherries, hackberries, and black walnuts have been recovered. Hundreds of places are known to have been visited or occupied by the Apache in the Sandhills, with the best known being Humphrey, a small village along the Middle Loup River.

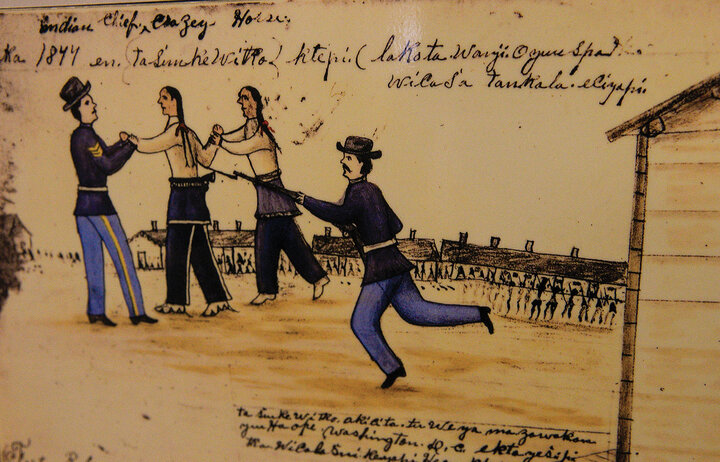

To the east, the Pawnee, operating out of large earth-lodge towns in the lower Platte River and Loup River basins, conducted bison hunting forays into the eastern and central Sandhills. This may have led to competition for hunting territory, perhaps explaining Apache abandonment of the area by the 1700s. Other tribes such as the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapahoe, Crow, Comanche, and Kiowa also hunted and traveled through the Sandhills, though they left virtually no archaeological signature. Interactions among these tribes and their use of the Sandhills continued much the same up until the development of the area for cattle ranching and subsequent European settlement.

We really have only just begun to understand the relationship between ancient people and this remarkable landscape. The story is not an easy one to tell, in that so many of the details remain unknown. While it is tempting to assume the Sandhills only provided Indigenous groups with an abundance of bison hunting territory, the reality is far more complex. The Sandhills offered a vast array of fish, birds, mammals, and reptiles for food, tools, and ornaments. Stream floodplains, lakeshores, and marshes, supplied by the groundwater reservoir, provided opportunities for productive wild plant collecting and horticulture, possibly persisting even in times of drought. With its enormous size and so many remote places, the region provided an excellent opportunity to avoid conflict and hostility with other groups. In this sense, the Sandhills might have served as a refuge of sorts. Of course, the opportunities presented by the Sandhills were no doubt matched by a number of challenges. Even with today’s technology and modern transportation and communication networks, life in the Sandhills can be difficult and isolating.

Sandhills archaeology is much more than a collection of beautiful spear points and ceramic vessels. It is an ongoing quest to understand how people adapted to this vast and unique region through time and space. The region remains ripe for exciting and productive archaeological research, with its ancient surfaces preserved deep under sand. However, as more sites are exposed as a result of continued erosion or discovered ahead of development, it is important to remember that such places are finite and truly nonrenewable resources. As opportunities to explore these places arise, we must weigh preservation with unlocking the secrets they hold and continue to emphasize a multidisciplinary approach. Only by taking into consideration studies involving geology, the past climate, and the past environment can archaeology help us to understand how the earliest central plains inhabitants experienced the Sandhills thousands of years ago.